The Human Eye is like a telescope in that it contains two lenses to focus light onto the retina. The first “lens” is the cornea which is a transparent, dome-shaped structure covering the front of the eye. It is a powerful refracting surface, accounting for 2/3 of the eye’s focusing ability. Because there are no blood vessels in the cornea, it is normally clear and transparent. Like the crystal on a watch, it provides a clear window to look through. To the observer, it glistens due to the constant bathing of tears equally spread onto its surface with each blink of the lids.

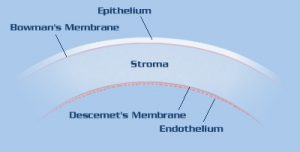

The cornea is tough, difficult to penetrate and is extremely sensitive – there are more nerve endings in the cornea than anywhere else in the body. For this reason, a corneal abrasion is generally very painful but fortunately, heals rapidly. The adult cornea is only about 1/2 millimeter thick and is comprised of 5 layers: Epithelium, Bowman’s membrane, Stroma, Descemet’s membrane and the Endothelium. Throughout life the cornea must remain transparent, smooth and of regular curvature to properly transmit and focus light as it enters the eye. Infections, trauma, or dystrophic conditions can involve any layer of the cornea and may result in scarring, thinning or curvature distortion that, if severe, can cause loss of transparency, optical distortion and blindness.

|

| Cross-section of the cornea. The normal cornea is about 0.55 millimeters (mm) thick in its center and consists of five microscopic layers as labeled above. The thickness may increase to 0.68 mm or greater if swelling occurs because of endothelial cell loss. |

We are born with a complement of cornea endothelial cells (3000 to 3500 cells/ mm²) that line Descemet’s membrane. These cells are responsible for “pumping” fluid out of the cornea, maintaining cornea transparency. As we mature, the concentration of these specialized cells may decrease by 1/3 but this quantity is still sufficient to maintain corneal clarity throughout life. Unfortunately, corneal endothelial cells are one of the few cells in the human body that are not capable of regeneration and if damaged or lost are not replaced.

If the cornea endothelial cell concentration falls below a certain critical threshold, as can occur in Fuchs’ Corneal Dystrophy, after cataract or cornea transplantation surgery or after eye trauma, the cornea swells and loses transparency leading to blurry vision or eventually, blindness.

Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy is a progressive condition that gradually affects both eyes. It is slightly more prevalent in women than in men. The condition rarely affects vision until people reach their 50s and 60s although an eye doctor can sometimes detect the early signs of Fuchs’ dystrophy at age 30 to 40 years. The pathology in Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy is demonstrated by increasing concentrations of optically degrading tiny dimples which form within descemet’s membrane in between the endothelial cells. The endothelial cells are gradually lost over the years.

At first, a person with Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy may notice subtle deterioration in night vision. As the process progresses, they may awaken with blurry vision that gradually clears later in the morning or later. The reason for this is during sleep the closed eyelids prevent evaporation; once the patient awakens, the open eyelids allow corneal surface evaporation to occur, allowing the cornea to thin and vision to improve. As the disease progresses further, corneal swelling will remain constant and vision remains poor throughout the day.

Eventually, the epithelium also swells with fluid and may form tiny blisters, causing eye irritation, foreign body sensation and severe visual impairment. If these blisters burst they can cause severe pain. These symptoms are also seen with other causes of corneal endothelial failure due to cataract surgery, corneal transplant rejection/late failure, or trauma.

To treat the disease, your doctor may initially try to reduce corneal swelling with hypertonic salt drops or ointment which temporarily extracts the fluid from the cornea. If the condition becomes painful, bandage soft contact lenses may be used. In early stages of this condition, a hair dryer held at arm’s length and directed parallel to face can be used to dry and thin the cornea. This technique may briefly improve symptoms and can be repeated if necessary.

Once the disease interferes with daily activities because visual performance is consistently reduced and/or persistent pain occurs, your doctor may recommend corneal transplantation to restore sight and eliminate discomfort.

There are other conditions of the cornea where the endothelial cells are healthy but the cornea may be scarred, abnormally thinned, warped and distorted. As a result, the light passing through the cornea is not focused as it should. This occurs in advanced Keratoconus, LASIK-induced ectasia (thinning), Radial Keratotomy (RK) induced irregularity, traumatic injury, or various corneal dystrophies.